Are Your Pricing Tiers Doing Their Job?

This is a guest post by Steven Forth, Co-Founder at Ibbaka Performance.

Many companies use tiered offers to organize packages and to define pricing. This is especially common with subscription models and in the SaaS business. Getting these tiered designs right is mission-critical for growth-stage companies. It is something easy to mess up, and even when you get it right, it can be hard to keep the tiers in focus.

Why have tiers anyway? There are three key reasons to do this:

To address different persona and use cases

To cover demand at different levels of willingness to pay

To provide an adoption path from one tier to the next (upsell path)

There can be some overlap with these, but you will make your life easier and your pricing design more coherent if you focus on just one.

Addressing Different Persona

Use packages to focus on different personas when buyers get value in fundamentally different ways. One may not even want to call this a tiered pricing offer, as the best solution is generally a different package for each persona. Focus on the functionality that drives value for the persona and ignore what does not. Some growth companies will be disciplined and only sell to one persona. Others will want to serve more than one persona, especially when the strategic game is to develop a platform.

(A platform exists when a solution provides value to two or more different groups, and each group creates value for the other group. Credit cards are a classic platform business, as is search and search marketing or online marketplaces connecting buyers and sellers.)

Covering Differences in Willingness to Pay

Sometimes buyers all get value in the same way but have different willingness to pay (WTP). This is generally because the details of their business models mean the value is larger or more important for some buyers than for others. This is the most common reason to use a tiered architecture.

There are generally two challenges here. Fencing the tiers so that buyers with a higher WTP go to that tier and getting the price-to-value ratios right across the tiers.

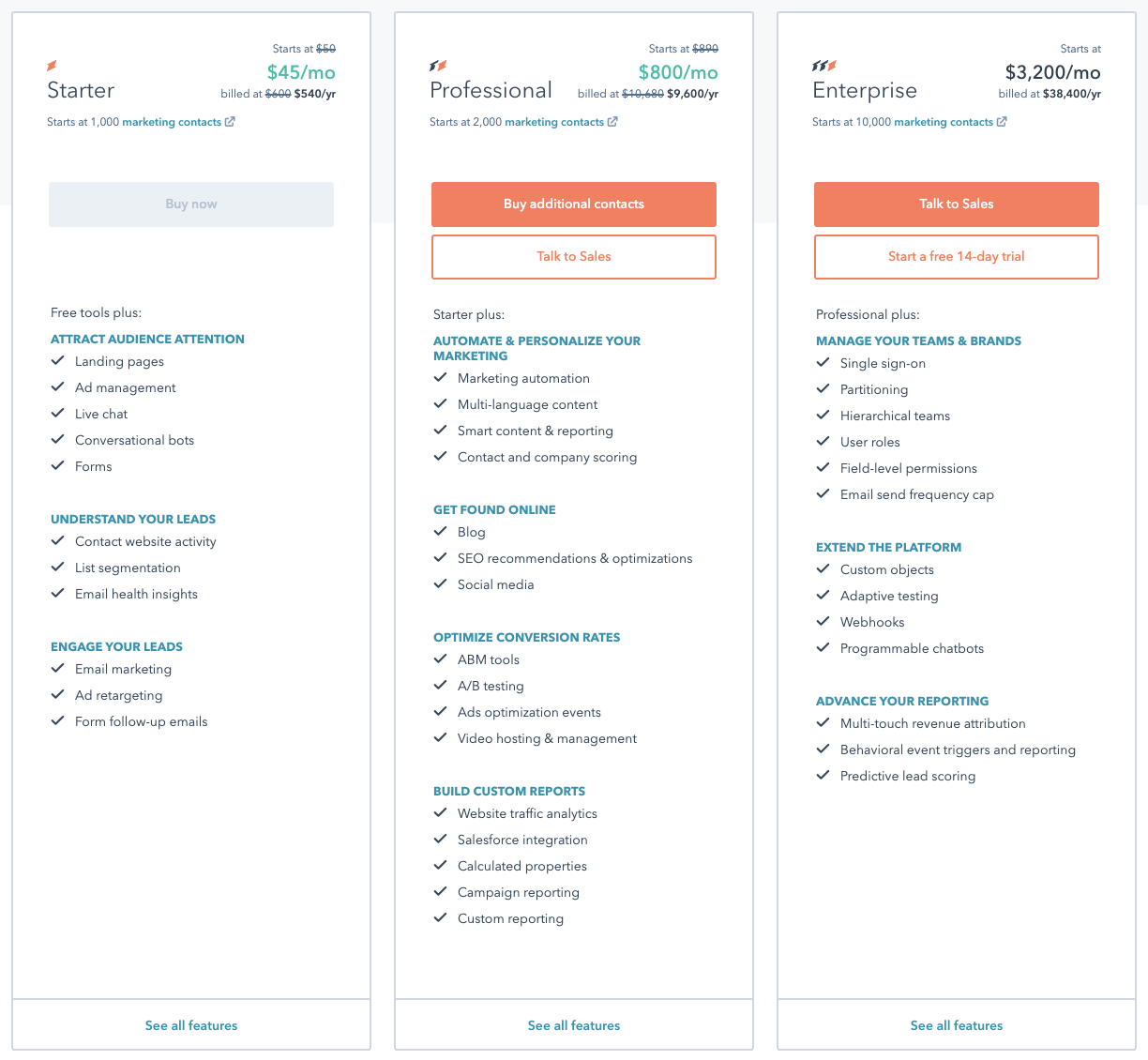

Fences are the metrics that one uses to guide a buyer to the correct tier. Look at Hubspot's pricing page. Can you see the fences?

They come in two flavors: consumption fences and functionality fences. For Hubspot, the critical value metric is around contacts (the value metric is the unit of consumption that tracks value). Hubspot uses this metric as a fence. Note how the price per contact changes across the tiers, from just 4.5 cents per contact for the Starter to 40 cents per contact for Professional and then down slightly to 32 cents per contact for Enterprise. Why would they do this, and why would buyers accept it?

The answer, of course, lies in the functionality offered at each tier and the value of a contact. The Professional tier layers in a lot of functionality, and with them comes a lot of additional value. The Enterprise tier is a lot more expensive, but rather than a deep discount on the price per connection (which many large enterprises would expect or even demand), there is a modest discount and a lot of the integrations and other user management functions that large organizations need.

When studying many-tiered architectures, one finds three common patterns:

1. Value is constant, but WTP goes up across the tiers. This is the hardest pattern to design for and requires a lot of understanding of the value drivers that determine the WTP. Ask, “What value drivers underlie the difference in WTP, and how can I only offer these to the buyers that value them?”

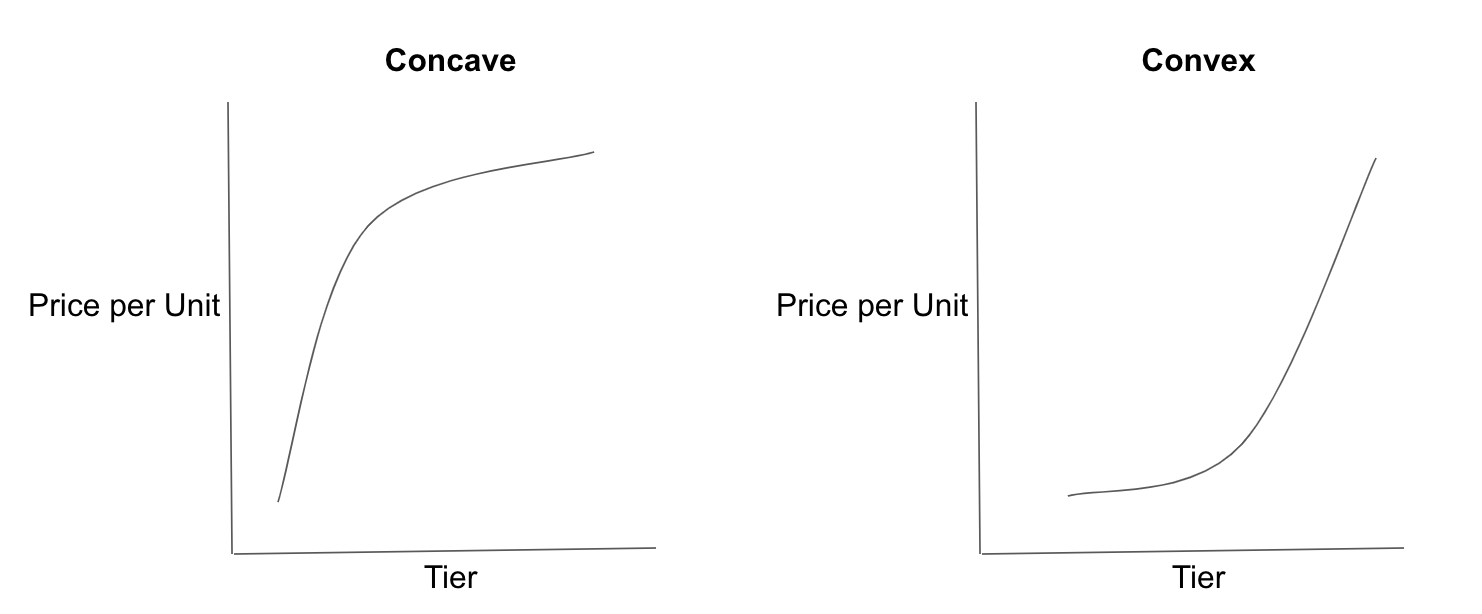

2. Value goes up across tiers, but the price to value ratio stays constant. This is the most common pattern, and it is the easiest to package and price. It also suggests certain laziness on the part of the pricing designer. In this case, ask, “Should I really be capturing the same percentage of value across tiers?” ‘Could I optimize for volume or revenue with concave or convex pricing?”

The choice of a concave or convex pricing curve generally reflects the structure of the market. When most of the targeted opportunity is at the top end of the market, a concave pricing curve is generally called for. When the opportunity is larger at the bottom end of the market, convex pricing tends to work better.

3. Value goes up across tiers, and the price-value ratio is lower at higher tiers. This is usually the result of a framing effect, where there is a psychological price ceiling. “No one will pay that much!” It can also be part of a strategic decision to over-serve (provide more value to) the customers that get the most value.

This pricing model is often seen in companies following a service-led growth strategy in which there are other ways to capture the value being created by the subscription to the software (see Pricing for Service-Led Growth).

Guiding Buyers Across an Adoption Path

Design to capture different WTP is only half the story. In many cases, the goal is to draw users in by providing a light offer and then upselling them to higher prices and higher value offers.

To make this design strategy work, one has to have a very clear understanding of the role of each tier and make sure the tier is actually performing the intended role. When we test this, we find this is seldom the case.

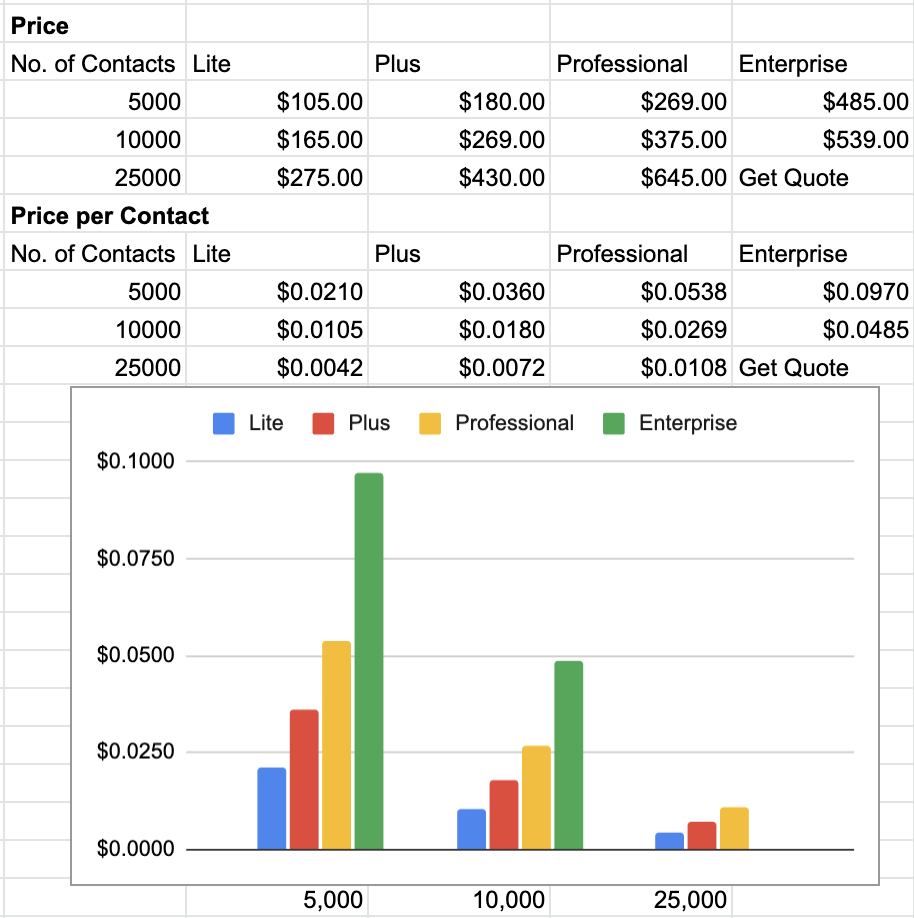

Let’s look at another marketing software company, ActiveCampaign. Here there is a strong suggestion that they want to lead you to a Professional subscription (the other way companies often signal this is the phrase “Best Value.”

Once again, the pricing metric is contacts, but this case is more complex—the relationship between tier and price changes with volume.

Tiers in a Standard Model and How They Might Be Used

Free

Free is popular these days. It only makes sense in a platform or community model. In a platform model, one may have part of the market that one has decided not to monetize— Google monetizes Adwords but not search. In a community model, the more community members, the greater the value created for paying members. LinkedIn users, who do not pay, create value for LinkedIn Premium users, who do pay. Of course, LinkedIn is also a market for recruiters and advertisers, so it is a hybrid model.

Free Trial

Many people today want to try before they buy, even in B2B. Some form of free trial is common. The challenge here is to decide how to limit the trial: by functionality, by volume, by time? Whatever approach is taken (and one can combine more than one), the goal is to demonstrate value while not letting the customer capture the value.

Entry

This is meant to be the first purchase. It whets the appetite without satisfying the hunger. Customers are meant to enter here but not to linger. Again, the trick is to provide enough value that people don’t leave (churn) while making it obvious that a lot more value is available.

Standard

This is often the target offer, the destination you are trying to get people to. A lot of value is provided, and the price is reasonable. The Premium tier is then used as an anchor to make the price seem reasonable by setting a high reference point.

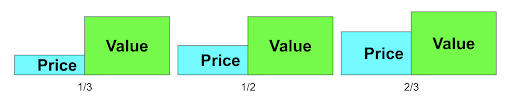

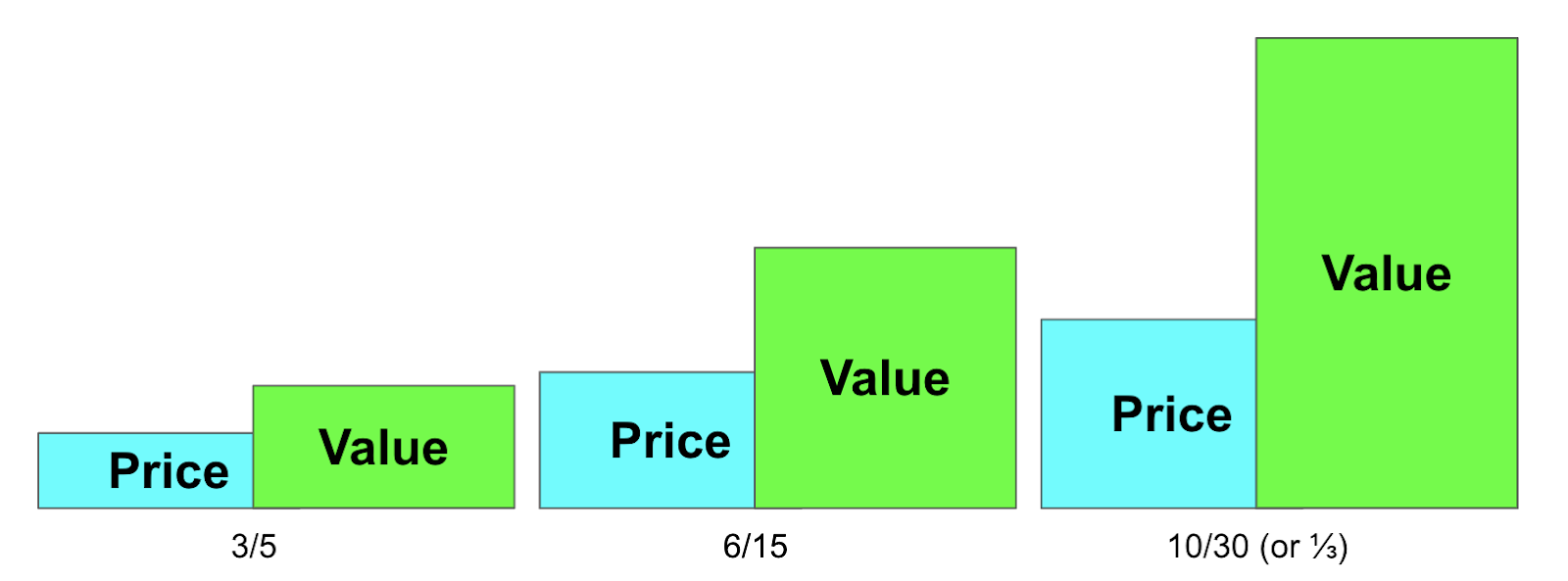

When the Standard offer is the target, the price-value ratios might look something like this:

Premium

In some pricing designs, it is Premium that is the target tier (the tier that one wants to guide buyers to). In other designs, Premium is a framing device to increase the perceived value of Standard. It cannot be both. In the above example, Premium (far right) is being used to frame Standard and is not the target. If it were the target, the pricing would look more like the below.

Custom (or Enterprise)

Published prices tend not to work well for large enterprise deals. So many companies have a tier for these large customers where one has to talk to a salesperson and where a price will be set by negotiation (we saw this above with ActiveCampaign).

Optional Functionality

In many cases, there are special classes of functionality that cut across the persona and tiers and have their own value propositions. Don’t be shy here. There is nothing wrong with offering optional functionality that is priced on its own pricing metric. At Ibbaka, we do this with our competency modeling environment, which can be purchased independently of skills profiles and uses the number of competency models as a value/pricing metric.

Build-in Assumptions and Test, Test, Test, Revise

It is impossible to get pricing perfect out of the box, and even if you did, the market would quickly evolve, making your pricing out of date. Pricing is not ‘once and done.’ We often see tiered pricing models that may have once made sense but have drifted and are no longer fit for purpose.

One common symptom is that the users are pooling in the Entry tier. In most cases, this is a suboptimal outcome. It happens when too much value is offered at too low a price. This is often in response to a churn problem, where Entry is serving double duty as a retainment offer.

To avoid this, and keep your tiered pricing in alignment with your strategy, try the following.

Be clear about the design strategy, optimizing across willingness to pay, or guiding buyers to the target tier (do not try to do both).

Set targets for volume and revenue for each tier.

Set ratios for the relative volume and revenue contribution of each tier. This is critical in order to optimize for WTP strategy, plus it is informative in both strategies and will tell you if the tier is doing its job.

Set conversion targets between tiers. This is most important when guiding buyers along an adoption path, but it also provides insights into tier performance, and having a target (or at least an assumption) makes it easier to assess the performance of the design over time.

At Ibbaka, we encourage our customers to check these targets/assumptions weekly, though depending on the cadence, one might want to do this daily or monthly.

One generally wants to see three data points to establish a trend (test, test, test), and once the trend emerges, consider making adjustments (revise).

Good pricing implements a strategy and adapts to change. When using tiered pricing, make sure that your packages and pricing are implementing a clear strategy and that you are making course corrections as the situation changes.